Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking that arise when our minds use shortcuts. These shortcuts help us make decisions quickly—an advantage when time is short or situations are urgent. However, the trade-off is that our “fast” thinking can lead to distortions in judgment.

When children learn about cognitive biases, they learn that their minds can mislead them. This helps them practice self-reflection. They start to see that quick assumptions—about people, outcomes, or events—aren’t always accurate.

By pausing to ask questions like, “Could my mind be fooling me?” and “Could there be something I am not seeing?”, children lay the foundation for a more thoughtful approach to learning and decision-making.

Examples of Cognitive Biases

A few common cognitive biases include:

The Clustering Illusion

If you were playing a game with a friend and they rolled six three times in a row, you might suspect cheating. However, true randomness can produce runs of the same outcomes by chance.

The Clustering Illusion is the tendency to perceive significance in random clusters of events. Although these clusters often occur by chance, our brains are wired to seek order and explanations, which can sometimes lead us to see patterns that aren’t there.

The Halo Effect

The Halo Effect occurs when a single positive (or negative) characteristic of a person or thing “spreads” to color our entire impression of them. For example, if someone is physically attractive, we might assume they are kinder or more intelligent than they actually are.

Conversely, if one negative trait stands out, we may unfairly judge all their other qualities in a negative light. This bias impacts how we form quick judgments about people in everyday life.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Sometimes, we continue investing time, money, or energy in something even if it’s not working out solely because we’ve already put resources into it. The hesitancy to give up on something because we’ve invested in it is called the Sunk Cost Fallacy.

Some examples are watching a dull movie just because you paid for the ticket or sticking with a book you dislike because you’ve already read half of it. Instead of recognizing that past investments are gone and focusing on what’s best for the future, we let the fear of “wasting” our initial investment trap us.

The Anchoring Effect

Imagine you and a friend walk into a new coffee shop. You see a sign saying a large coffee costs $9 and think, “That’s expensive!” However, your friend first noticed that a medium coffee costs $8. When they see that a large coffee is $9, they think, “The large coffee is only $1 more—that’s a great deal!”

This difference in perspective is an example of the Anchoring Effect. Our first piece of information (the “anchor”) can shape how we judge subsequent information.

Why Should Kids Learn About Cognitive Biases?

The ability to identify cognitive biases helps children not just academically, but in personal relationships and everyday problem-solving. For example, understanding the Halo Effect can help children avoid making snap judgments about others, and recognizing the anchoring effect can improve decision-making skills.

An overconfident child who never learns about the pitfalls of intuitive thinking may carry that overconfidence into adulthood, overlooking important details or dismissing perspectives that challenge their own. This can lead to judgment errors. By contrast, a child who understands how easily the human brain can be tricked develops healthy skepticism — a quality that paves the way for more informed, rational decisions later in life.

In the digital age we have access to more information (and misinformation) than ever before, and cognitive biases affect how we seek out and interpret information. For example, confirmation bias — the tendency to favor information that aligns with preexisting beliefs — may result in us ignoring opposing viewpoints. Learning about cognitive biases early prepares children to be informed, responsible digital citizens.

How Can We Teach Kids About Cognitive Biases?

A good starting point is to show students that anyone can be fooled. The “Bat and the Ball Puzzle” is a classic example:

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 together. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

Most people immediately answer “ten cents,” but that’s incorrect. If the ball costs ten cents, the bat should cost $1, which is only 90 cents more. The correct answer is five cents. This puzzle highlights how our snap judgments can mislead us. Once students see that everyone makes these thinking errors, they’re more open to learning about biases.

Stories are an excellent way to teach kids about cognitive biases. Stories bring abstract concepts to life, and asking children to write or share their own examples allows them to connect these ideas to real-world situations. Here’s an example:

Casey was excited to buy a new board game called “Treasure Quest.” She saved her allowance and spent all of it on the game. She invited her friends over to play, but she quickly realized the game wasn’t what she expected: the rules were complicated, the pieces kept falling over, and it was causing arguments and stress. Nobody was having much fun. Still, Casey insisted they keep playing—and every time her friends suggested packing it up, Casey protested.

The next time her friends came over, she insisted on playing the game again. Her friend Liam finally asked, “Why do you want to keep going if it’s no fun?” Casey replied, “Because I spent all of my money on it! If we stop now, that money will have been wasted.”

Can you see any mistakes in Casey’s thinking?

I recommend letting kids try to explain the error in their own words first, and then tell them the name of the bias. Teaching the names of the biases is important because it makes them easier to identify later. You can then ask how Liam could respond, and work together to write an ending for the story. For example:

Liam explained, “But your money is gone whether we play or not. We could do something else we actually enjoy, or try trading this game for a better one!”

Casey paused, realizing that finishing a game she disliked wouldn’t bring her money back. She agreed to stop playing and decided to exchange “Treasure Quest” for a new board game that she and her friends would enjoy.

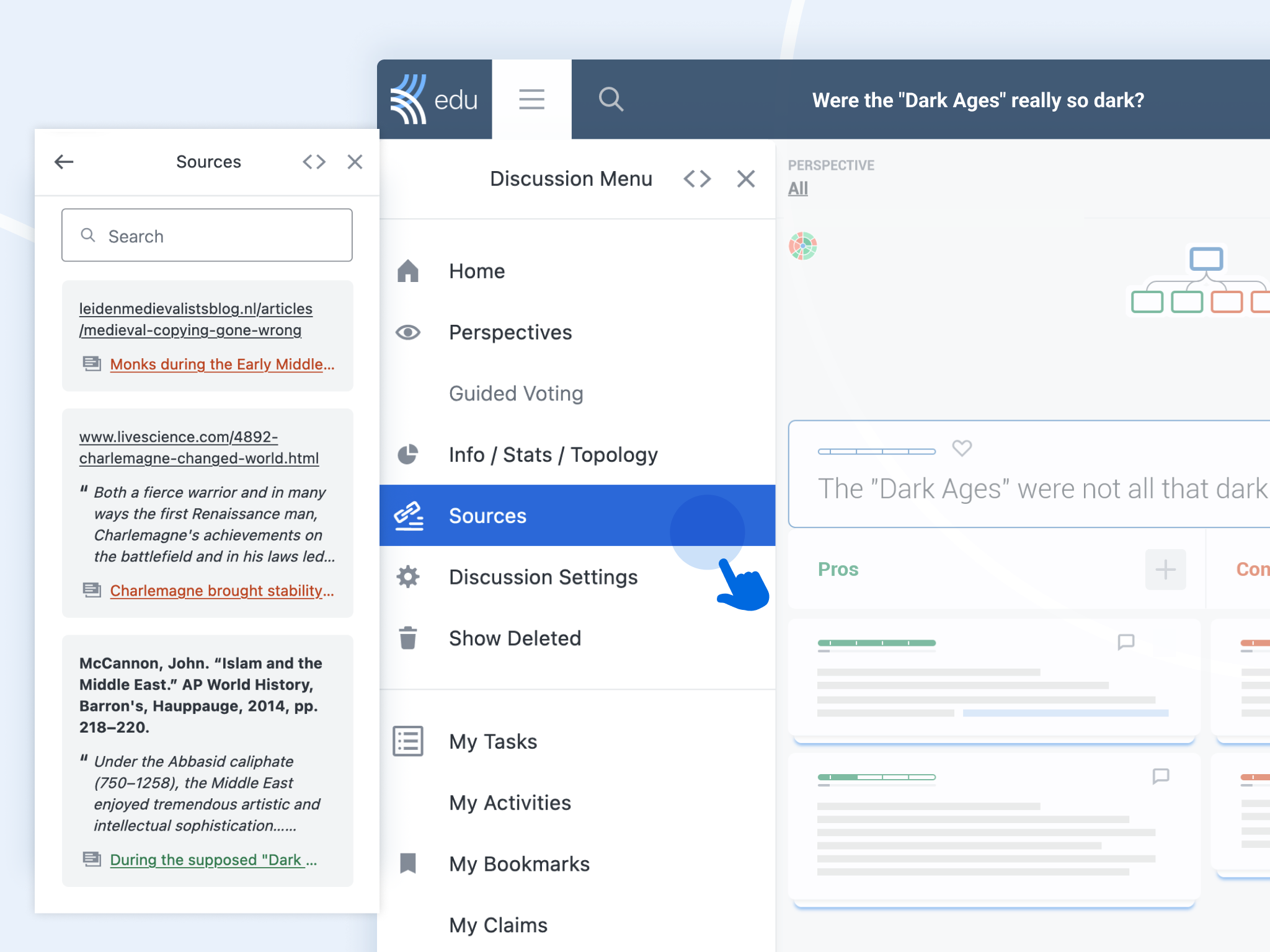

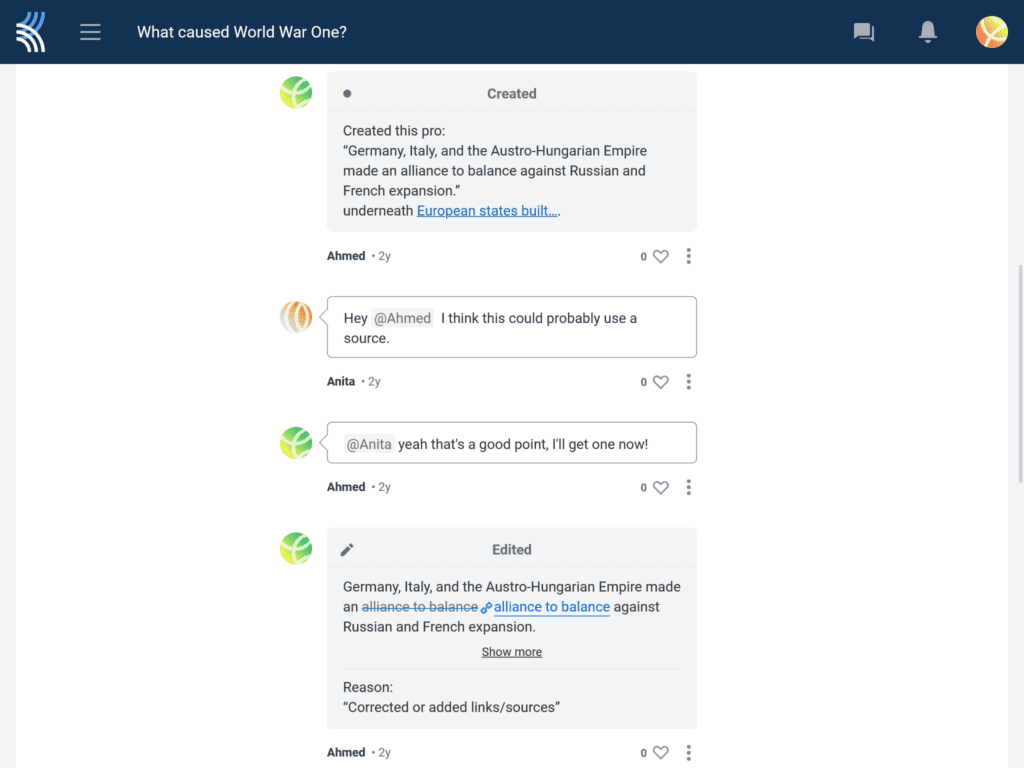

Another way to explore bias further is to use Kialo Edu to have free, engaging class discussions. On Kialo Edu, students can post claims (pros) and counterclaims (cons) on a topic and cite sources to back up their points. Tasking students to add multiple sources of evidence to their claims allows them to consider multiple perspectives on an issue.

Furthermore, as students read through their classmates’ contributions, they might encounter some arguments that reveal biases. Students can collaboratively refine a claim to ensure that such arguments don’t include such biases and are instead based on sound reasoning and evidence.

Finally, teachers can also post intentionally biased statements so students learn to spot flawed reasoning. This is a great way to help students build critical thinking skills in a controlled setting which they will later be able to apply in the real-world.

By teaching kids about cognitive biases, we help them recognize that their minds, while incredible, aren’t perfect. Early awareness of how thinking can go astray helps children grow into critically thinking adults who question their assumptions, listen to multiple perspectives, and make more thoughtful decisions.

For more ideas and activities to help children develop critical thinking skills, head over to Critikid.com. There, you’ll find interactive, story-based courses about logical fallacies, data analysis, formal logic, and emotional intelligence, along with free puzzles designed to challenge assumptions.