Teaching students about logical fallacies is a vital step to help them become adept critical thinkers. Discussions are a great way to teach students how to spot logical fallacies, and you can use a 100% free discussion tool like Kialo Edu to do so.

Students who can identify common logical fallacies will have the tools to both build stronger arguments and identify faulty arguments out in the wild.

What are logical fallacies?

Logical fallacies are arguments in which the conclusion is the result of faulty reasoning. They are invalid arguments that can nevertheless sound convincing.

Arguments that can simply be disproved by facts are not logical fallacies. Logical fallacies have an error in how the argument is structured.

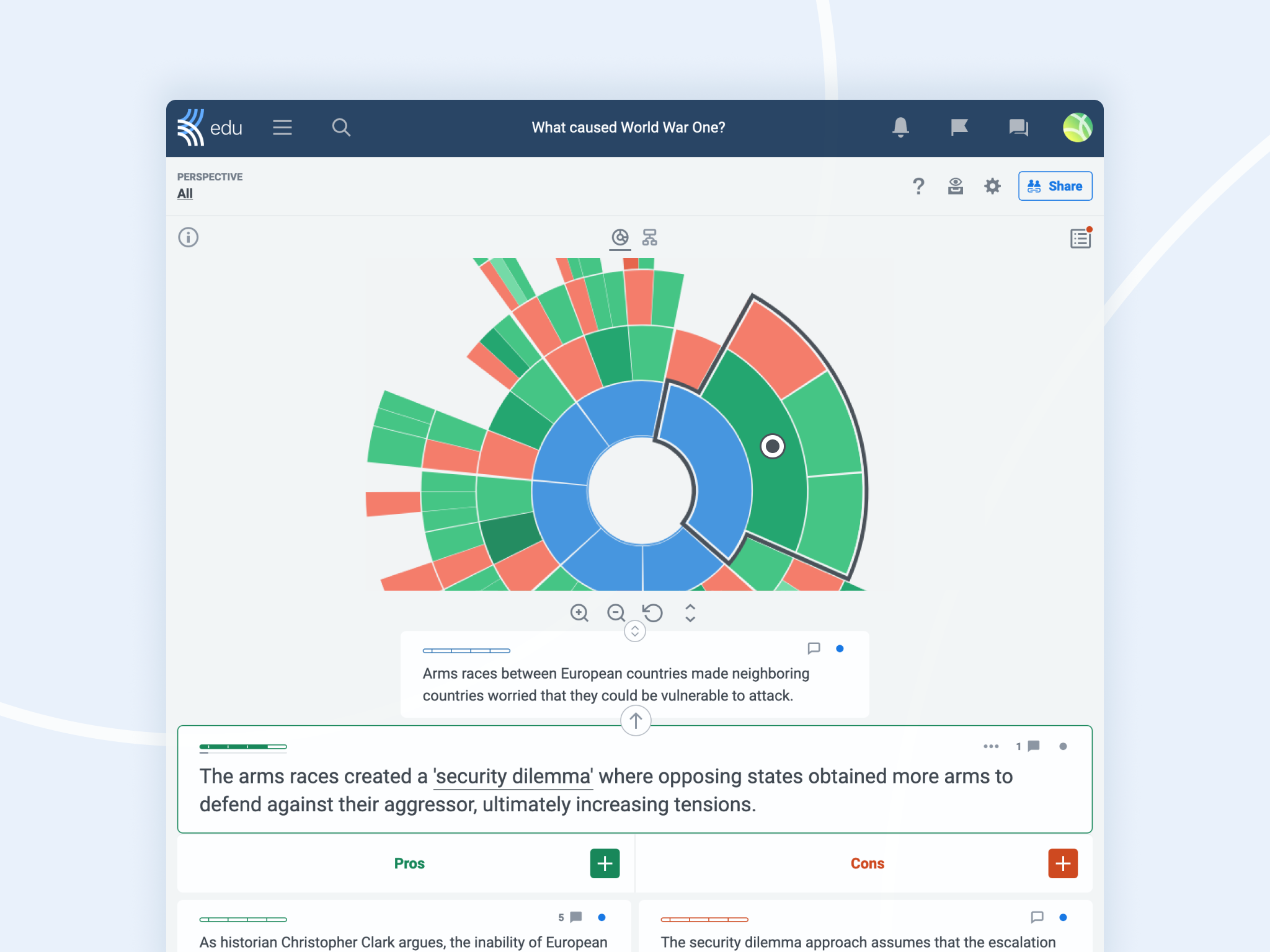

To help students learn about logical fallacies, you can try having a class discussion on Kialo. Helping students build clear, well-reasoned arguments is one of the great benefits of using Kialo for class discussions!

Our platform’s argument-mapping structure is designed to help students visualize and develop complex arguments, making it easier to avoid errors in thinking, from logical fallacies to cognitive bias.

To get a sense of how Kialo works, explore a class discussion from a student’s perspective and see how you can use engaging class discussions to teach students about logical fallacies!

How to identify common logical fallacies

Appeal to emotion fallacy

As the name suggests, the appeal to emotion fallacy is an argument that relies on stirring up an emotional response in its audience to compensate for the lack of sound reasoning. You’ll find this fallacy everywhere, from over-sentimental advertisements to political rhetoric.

Sometimes outright appeals to emotion are easy to spot. Take this example of a politician’s expressive language:

“If my opponent wins, dark days are ahead. But vote for me and you will be able to breathe easy again!”

Metaphors, analogies, and evocative imagery are often used to appeal to our emotions but can be misleading if they aren’t backed up with facts and data.

Likewise, arguments based on anecdotal evidence or imaginative storytelling often rely on the appeal to emotion. We naturally empathize with the characters in stories, but students should be wary of generalizing arguments based on emotive responses.

Appeals to authority fallacies leverage the supposed authority of a third party to persuade an audience. Often, the accredited authority is questionable or downright irrelevant to the point being made.

Take the example:

“My teacher has a PhD in Education and she says you shouldn’t drink coffee because it’s bad for your health.”

In this case, the speaker is not only failing to provide any argument for why coffee is bad for your health but also the supposed authority doesn’t have any expertise in this subject!

Students should first identify whether the argument relies on the authority of the person invoked. If so, they should assess the credibility of the given authority.

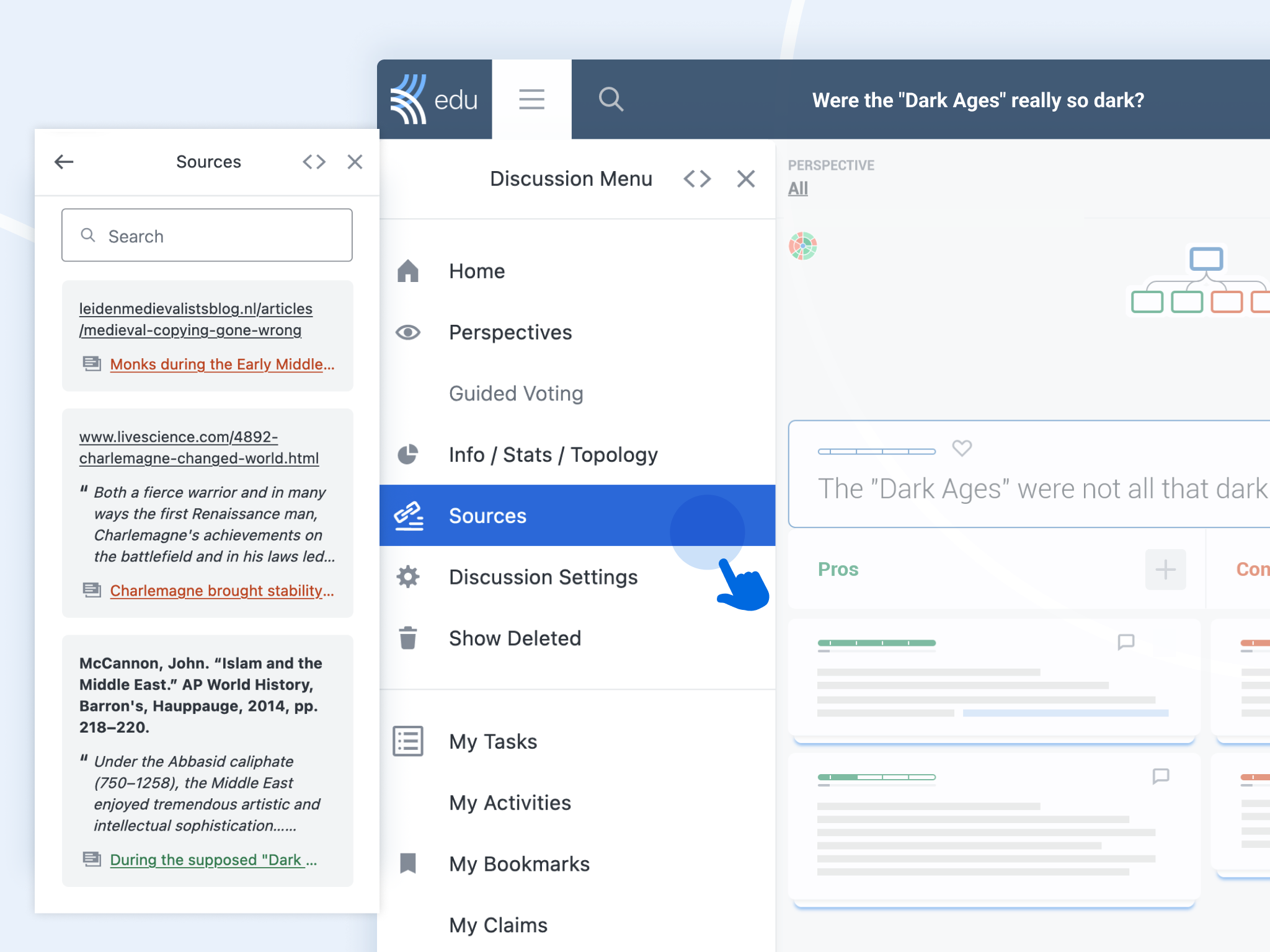

When writing essays (or claims on Kialo Edu), students should properly cite sources so that any appeals to authority that they make can be checked by readers. Students should be able to justify their choice of references and practice investigating claims accredited to others, to better avoid fallacious appeals to authority.

False cause fallacy

The false cause fallacy occurs when one incorrectly assumes a causal connection between two events. Take this example:

“Every time I wear these socks, I get a great result on my test! So these socks must be lucky.”

Here, the speaker is drawing a causal link between the socks and the test results without any proof. The false cause fallacy is captured in the academic adage “correlation is not causation.”

Students should be on the lookout for claims of a causal relationship between two events when there isn’t conclusive proof that one causes the other. They should be particularly dubious in cases where there isn’t even an attempt to explain the process by which the first event influenced the second.

When talking about possible causal relationships, students should use qualifiers like “might,” “may,” and “could” to acknowledge that there isn’t a proven connection. These arguments will be stronger since they avoid the false cause fallacy.

Slippery slope fallacy

The slippery slope fallacy suggests that once a particular thing happens, it will inevitably lead to something worse.

To identify the slippery slope fallacy, students should investigate whether a predicted chain of events is justified. Slippery slope arguments often also rely on the appeal to emotion, playing on the audience’s fear of the more extreme consequences.

Being clear-headed about the difference between the necessary and potential consequences of an event can help avoid making fallacious slippery slope arguments.

Straw man fallacy

The straw man fallacy involves misrepresenting the opposing position so one can argue easier against it — that is, creating a “straw man” that is easily knocked down. Let’s look at an example:

Student 1: I think school uniforms are good because they help build school spirit.

Student 2: So you think students shouldn’t be able to express their individuality and should all think the same thing?

In this case, Student 2 has completely misrepresented Student 1’s argument in order to make their position against school uniforms seem stronger.

To identify a straw man fallacy, students should recognize when an argument misrepresents or oversimplifies the opposing view. This also helps students avoid making straw man fallacies when they acknowledge and listen to opposing arguments, even if they are in disagreement.

When defending a particular position, students should try to consider the “steel man” argument against their point. To create convincing arguments, students should try to refute the strongest possible counter-argument.

Try having an engaging class discussion today and guide students to avoid making logical fallacies when making arguments! You can also check out Kialo’s Topic Library of pre-made discussions, complete with a thesis and a few prompts to quickly get students discussing, whether on a curriculum topic or a casual subject that piques their interests.